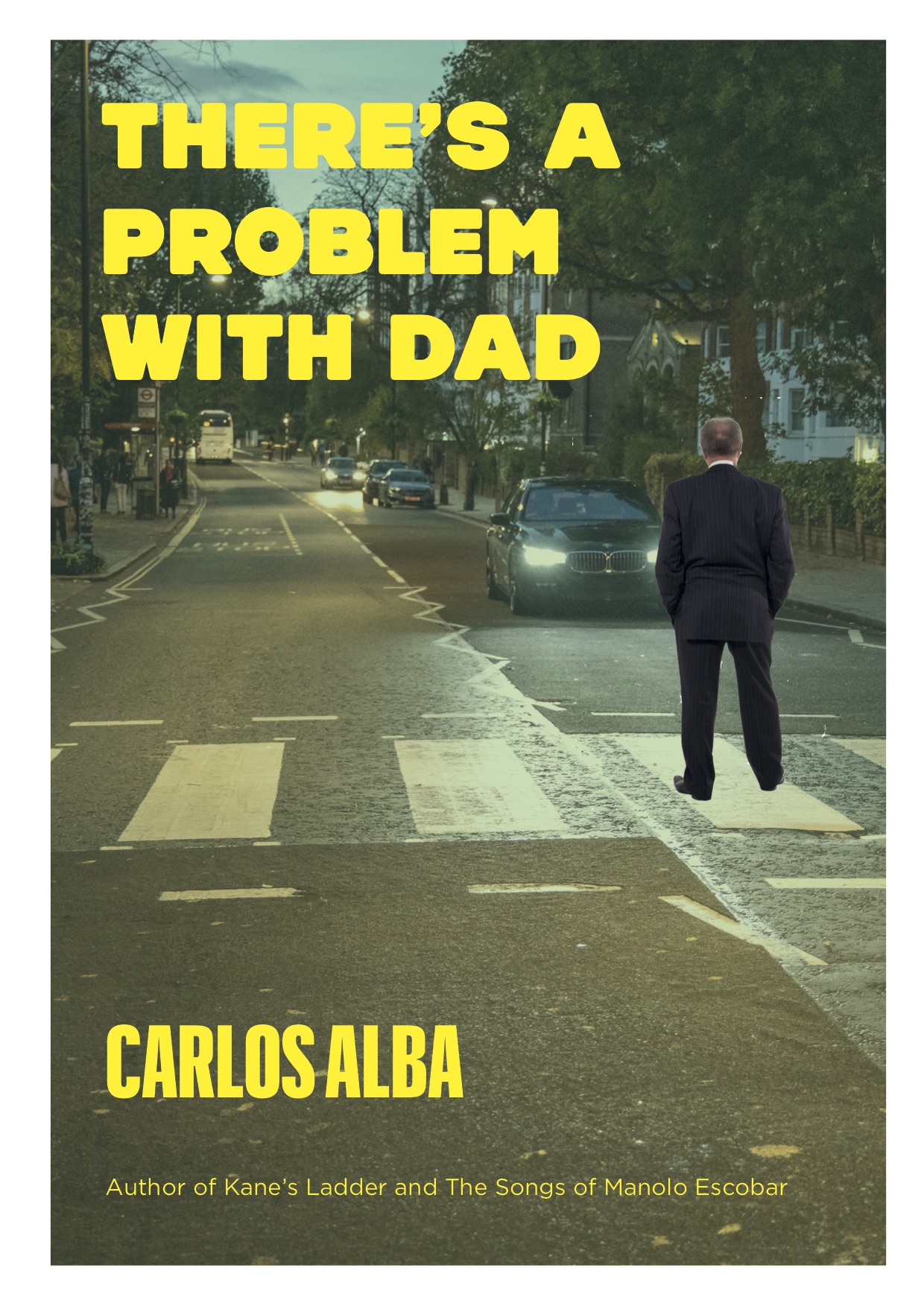

We asked Carlos Albla about his experiences and motivations for writing a book centred around undiagnosed autism. There’s a Problem with Dad is available to pre-order HERE and will be virtually launched on May 12th!

What was your motivation for writing the book?

In around 2010, we began to suspect my father-in-law, then in his late sixties, had undiagnosed, high-functioning autism. I was vaguely aware of what then was called Asperger’s syndrome when I read a book by a former journalist colleague, Sally Brampton, in which she described behaviours exhibited by her father, who remained undiagnosed well into his seventies, although she and other family members had long considered that he wasn’t what we now call ‘neurotypical’.

My father-in-law died in 2013, aged 70, and only in the last weeks of his life did he come to terms with his autism and accept that he probably was on the spectrum.

It was a great relief for my wife, Hilary, who had spent years feeling confused and often hurt and alienated by his seeming inability to communicate with her on anything but the shallowest level. While strangers saw him as polite and formal, those closer to him were constantly challenged to process and overcome what seemed like an often-destructive coldness and inhibition.

Like many people with high functioning autism, he was successful professionally, highly intelligent and articulate. As well as being curious, practical, and well-travelled, he seemed to excel in whatever he turned his hand to including mountaineering, marathon running and ballroom dancing. He was also solitary, friendless, humourless, highly routinised, unemotional and intractable.

His disengaged, deadpan reactions to emotionally engaged situations became the stuff of enduring family anecdotes.

When I told him I had been made redundant, he smiled and walked away. In restaurants he would get up after he had finished his meal, while everyone else was still eating, and wait for us in the car park.

He arrived on our doorstep at eight o’clock one Sunday morning and, without any formalities, asked to speak to Hilary. I told him she had gone into hospital the day before, suffering from chronic stomach cramps, and that she had been kept in overnight. After staring at me blankly for a few seconds, he said: ‘Can I borrow your mitre saw?’

There was, however, a much more serious side to such behaviour. Hilary suffered enormously from having a father who was seemingly incapable of expressing or demonstrating emotion. If she tried to hug him, he became visibly discomfited and the closest he came to telling her that he loved her was, shortly before he died and confined to his bed, he said that she and her brother, Paul, were his greatest achievement.

You’ve written two books before. Are there any differences in the way you’ve approached each story?

My first two novels, Kane’s Ladder and The Songs of Manolo Escobar, were about childhood and adolescence, respectively, and there was much more of ‘me’ in them. Preparation was largely about trying to remember what it was like growing up in the 1970s and 80s. They were family stories and my main aim for both was to make them warm and funny.

There’s a Problem with Dad, or TAPWD as it became during editing, was about addressing an issue – the impact of undiagnosed, high-functioning autism on older people and their families – and, while there are funny moments, it’s a serious book about a serious subject.

I was conscious from the start that I needed to write something that people in the situation I was describing would recognise and so there was a greater responsibility to research the subject as thoroughly as possible, not just so that they would enjoy the book but also that they would see it as authentic and legitimate.

What do you owe the real people upon whom you base your characters?

All writers take elements from their own lives to use in their stories and as long as they are used to inspire fictionalised characters and events, then no great harm is done. Of course, there are situations when people object to seeing themselves barely reimagined in a less than flattering light in the pages of a novel and take umbrage.

Writing TAPWD was different because of the serious and sensitive issues involved and I thought long and hard about using the neurology, as I perceived it, of a family member – even one who had since passed away – as the basis for a story.

I had to consider the effect it might have on people who knew and loved that person and, if they objected to me writing about them, was that sufficient reason not to address the issue?

While my father-in-law was undoubtedly the starting point for George Lovelace, the character evolved during a lengthier journey.

What do you hope readers take away from your book? / What impact, if any, do you hope your book has?

I hope it strikes a chord with people who know someone with diagnosed or undiagnosed high-functioning autism and that they will perhaps look at that person and their behaviour in a more understanding light.

When I describe George to people, many will say, ‘oh that’s my brother’ or ‘I think my father has that’ and it seems hardly a week now goes by without someone in the public eye revealing that they are on the autistic spectrum.

Asperger’s Disorder was first given a medical classification in 1994, and so a large but undetermined number of people have grown up without being diagnosed. Their behaviour is typically explained away as being part of their character – she is very set in her ways, he likes his own company, he doesn’t wear his heart on his sleeve.

Unlike their ‘neurotypical’ counterparts, autistic people don’t experience emotion in the same way and so they have trouble picking up on verbal and non-verbal social signals. Because they don’t understand the underlying meanings of certain words or actions, they miss the kind of social cues that most people take for granted.

That’s the reason why they don’t follow the normal rules of conversation, don’t get jokes or don’t appreciate the emotional impact or implications of certain situations or statements.

Like my father-in-law, they are often highly articulate people with successful careers who are exceptional only in the sense that they think differently from the neurotypical group.

How do you balance making demands on the reader with taking care of the reader?

Characters must be authentic with emotional and psychological consistency but having them behave in ways readers always expect is a recipe for a boring narrative. Writers have to find the tension between creating characters who are believable but not predictable and that involves throwing in occasional surprises and reversals which catch the reader off guard.

Taking care of the reader is quite a recent idea, I think, and I’m not sure I entirely understand it. Part of the joy of reading is to be taken to places that are uncomfortable – to be shocked and challenged and even offended. Being overly mindful of readers’ sensibilities would have denied us some brilliant recent fiction with unsavoury, misanthropic themes, such as Morven Caller, The Lovely Bones, We Need to Talk About Kevin and Secret History.

This year’s Booker Prize winner, Shuggie Bain, is unrelentingly brutal, but elevated by the warmth and humanity of its central character.

What advice do you have for other writers?

Just get something down in writing. You can spend the rest of your life planning and all the time you’re doing it, the blank page in front of you becomes ever more of a tyrannical reminder that you haven’t started yet.

Opening a file and seeing that you have already created several pages of text is massively encouraging, even if you know it’s not perfect. If you have ambition to be published, anything you submit is only ever going to be a first draft, so you need to get into the habit of discarding and rewriting. Part of the joy of writing is seeing how much more improved what you produce can be by thinking about it in different ways.

What’s your favourite novel/favourite author?

Oh Lord, it changes by the week. Naming my favourite author would be like naming my favourite food or Beatles song – it depends what mood I’m in.

When I find a writer I like, I’ll generally read everything they have written until I either run out of books or get bored with them, whichever comes first.

I’m currently nearing the end of Hilary Mantel’s Tudor triology and am nowhere near bored with the story. I think if she wrote another dozen in the series, I’d still be devouring them to the last – and The Mirror and the Light is over 800 pages. She’s an author whose words I read and I think, I could never do that.

Do you have any plans to write another book? If so, any hints/ideas?

Yes, I’m working on a novel about the arrival of the US nuclear submarine fleet on the Clyde in the 1960s and the impact they had on a local Argyllshire town.