by Kirsty Miller

Growing up, were you ever told by a teacher that you had to say “yes” instead of “aye”? Did you hear from adults around you that words like “ken” and “jaiket” were slang? Did you learn to regard the brilliant, wonderfully rich Scots language as unserious and embarrassing?

The idea that Scots is simply a slang version of English is a very damaging – but very common – misconception. 1.5 million people classed themselves as Scots speakers in the 2011 census, but there is still a pervasive belief in society that to succeed, and to come across as educated, you must speak English. This prejudice is one of the reasons my siblings and I grew up speaking English, despite having a mum who has spoken Scots since childhood; subconsciously, she wanted to protect us from the classist, disparaging comments she often faced in school. Although she taught us a lot of Scots, and I have a good understanding of the language, I hardly use it. Having noticed a recent development in the way Scots is discussed, I wanted to look at how our attitudes towards the language are shifting, and what consequences this has for Scotland’s literary future.

First of all, what is Scots?

Scots is an ancient language that is spoken in many parts of the country today. It came to Scotland with the Anglo-Saxons as English did, but although the languages have the same roots, they have always been distinct from one another. There are some aspects of the Scots language that make it complex and contribute towards the idea that it is not a language in its own right. For example, there is not a standardised way to write Scots, and there are many regional varieties; Scots is the overall term used to describe many different dialects.

Where did the negative ideas about Scots come from?

As a nation, we have a difficult relationship with the ancient languages we have inherited. Gaelic, which was spoken all over Scotland centuries ago, faced a long slow decline to near extinction. This was partly due to catastrophic events such as the Highland Clearances, which decimated the Highland population, and partly a result of repeated, deliberate attempts to ban and eradicate the language. Similarly, Scots was gradually abandoned in favour of English. It was once the language of kings and nobles in Scotland, but it came to be viewed as a corrupt version of English. Events such as the union of 1707 cemented English as the formal language of the country.

Many Scottish poets and authors wrote in Scots, including Robert Burns, who is known and celebrated worldwide. But when modern authors have used realistic Scots dialogue in their works, they have typically faced a lot of criticism. James Kelman became the first Scot to win a Booker Prize in 1994 with his novel How Late it Was, How Late,but there was a huge amount of controversy, much of which centred around Kelman’s use of the Glasgow dialect. However, there are encouraging signs that Scots is beginning to be perceived in a new way.

How are things changing?

There have been many adjustments which are having an impact on the way Scots is regarded in schools. The government’s Curriculum for Excellence recognises the legitimacy and importance of Scots, and in 2014 the SQA created a Scots Language Award, giving school pupils the opportunity to study it formally. These are vital steps in the attempt to change the way young Scots speakers view their language.

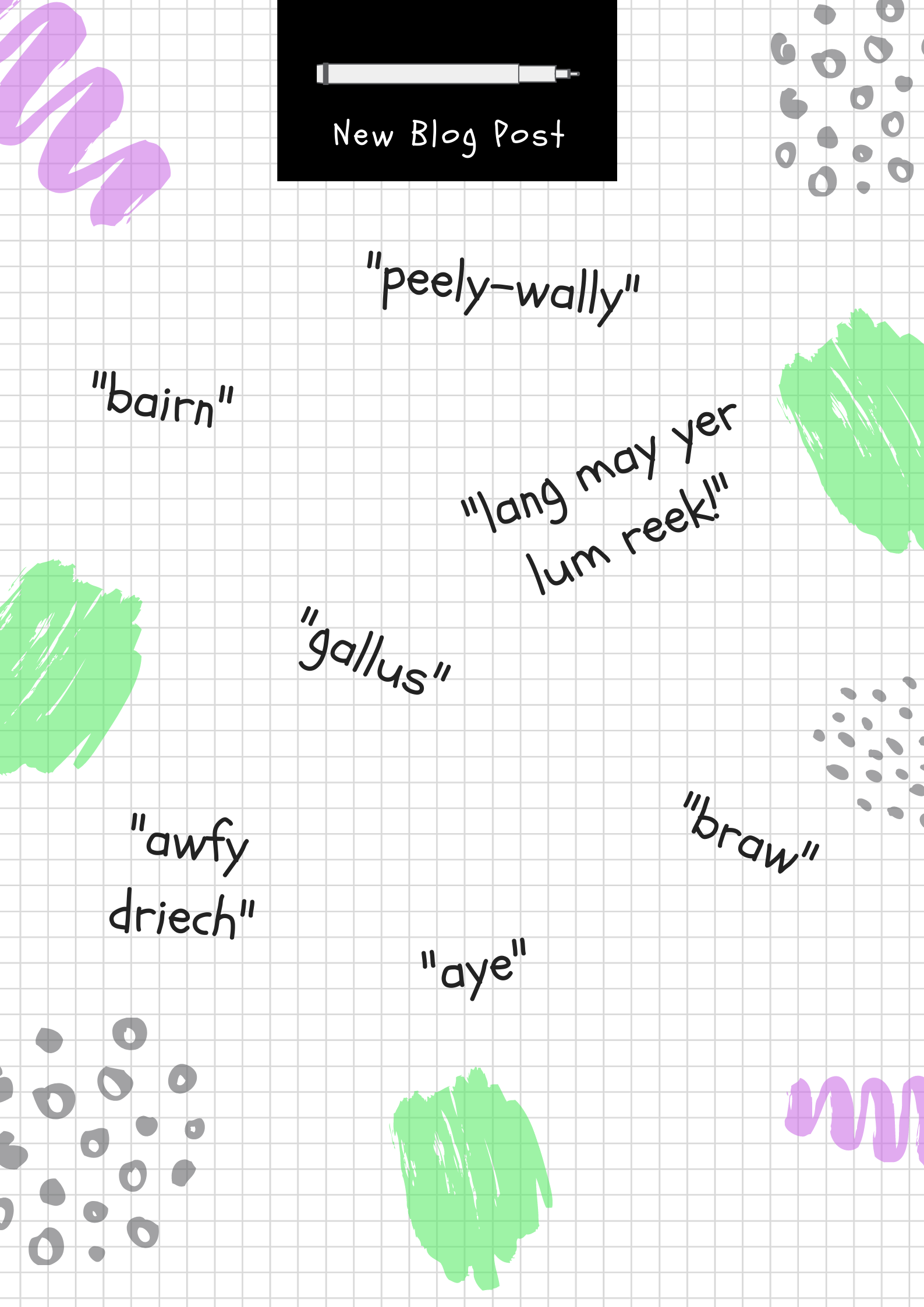

TV and social media are also helping to promote a new attitude towards Scots, with young presenters and poets leading the way. Alistair Heather is a presenter and writer who creates educational content in Scots for platforms like BBC’s The Social. Student Len Pennie is an amazing Scots poet who has amassed more than 78,000 followers on Twitter in the last few months. She uploads posts and videos in which she recites her poems, explains Scots vocabulary, and discusses regional varieties of the Scots language. Programmes and channels dedicated to Scots are giving people new ways to engage with the language and are driving positive change.

What do these successes mean for the future of Scottish literature?

Last year, Douglas Stuart became the second Scottish winner of the Booker Prize with his novel Shuggie Bain. While the novel is not written entirely in Scots, the language is featured extensively in the dialogue. Stuart’s comments on the impact of Kelman’s work are telling – in an interview, he explained that reading How Late it Was, How Late was a “life-changing” experience, as it was “one of the first times I saw my people, my dialect, on the page.”

The response to Shuggie Bain has been overwhelmingly positive, with many praising the use of the Glaswegian dialect this time. Hopefully, its success will encourage other new Scottish writers to utilise the language they are often most familiar with, and to never feel it is inferior or unworthy.