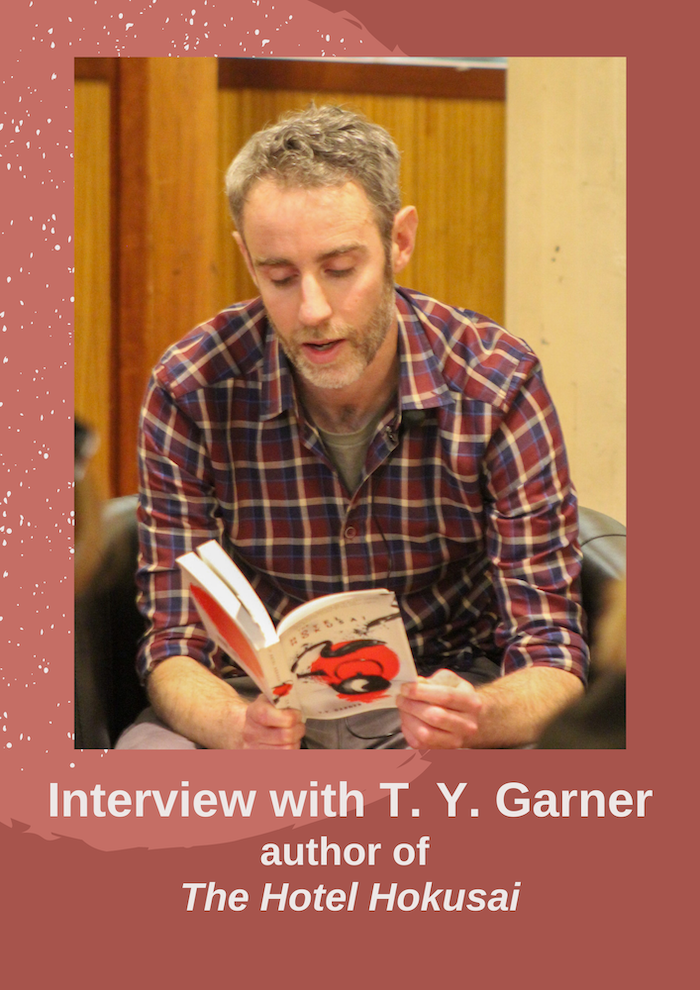

It’s been one month since the release of The Hotel Hokusai by T. Y. Garner! To celebrate, we’re sharing a full-length interview with the author, which covers everything from his inspiration and writing process to plot choices and thematic resonances. Enjoy!

Your upcoming novel The Hotel Hokusai is a murder mystery that explores a cultural crossover between Korea, Japan and Scotland. Could you tell us a little about where you got the idea for the book?

I lived and worked as an English teacher in Yokohama, Japan, where the story’s set, for about two and a half years between 2015 and 2018. Yokohama was Japan’s main ‘treaty port’, after an American navy commander forced the Japanese shogunate to open the country to trade in 1853. In the previous centuries of Japan’s ‘closed border’ policy, it was just a small fishing village, but it quickly became the focal point for an encounter with Western culture in which Scotland played an important part. Scotsmen like Thomas Blake Glover, who set up what would become the Kirin brewery, and Henry Brunton, who was commissioned by the Japanese as a lighthouse designer, were vital in the modernisation of Japan. The port area now is mostly modern skyscrapers, but if you pay attention there are lots of plaques and bits and pieces of older history. When I was there, I would wander round places like the foreigners’ cemetery up on ‘the bluff’, which is what they call the hill where the first foreign settlers built their houses. At the foot of the bluff, you cross a canal and come into Chinatown. The demarcation of different categories of foreigner: white European and ‘other Asian’ was apparent right from the beginning, and in fact the whole port settlement was Japan’s attempt to keep foreign presence within limits.

So, the settlement in this period had the novelistic attraction of being a self-contained place featuring all these different cultural elements. Then it was a case of finding the characters to write about. In my twenties, I worked in journalism and wrote a fair bit about the waves of migration from North Africa into Italy – all these people fleeing from desperate circumstances in search of safety and a new life, which is still going on now, of course. So, although it was a different setting, I was drawn to the idea of a young migrant in Japan who didn’t have the luxury of belonging to the European trading elite, who had to start at the bottom. And it made sense for him to be Korean, since Korea is one of Japan’s nearest neighbours and many Koreans did in fact make this journey across the sea in search of opportunity. Quite early on I hit upon the idea of him finding work as an apprentice to a grizzled Japanese vendor of fried eels. I have no idea really where that came from, but eels are interesting to write about! The other ingredient that really got the novel cooking was finding out that two Scottish artists, George Henry and E. A. Hornel, had spent a year in Yokohama in 1893. I remember the precise moment I found that out – I was on a crowded subway train scrolling the internet and I had that sense of ‘A-ha!’. What about fusing the story of a Scottish artist in Japan on an all-expenses-paid painting trip, and a Korean migrant eel vendor desperately trying to forge his future in a new country? So, I had Han, the young Korean, Archie, the Scottish artist, and the setting of Yokohama, but I still didn’t have much of a plot. Then on a visit to the Yokohama Archives of History, I came across a snippet in a newspaper from 1893 about a young Japanese woman found drowned in the harbour, the assumption being that she had committed suicide after failing to get a job in the telephone exchange. I’d originally been looking for any mention of the artists or something connected to the art world, but maybe it was the juxtaposition of the tragedy of a young woman’s death and the banality of the reason given for it that kept niggling at me. So, I ended up creating Tsubaki, a feisty young Japanese woman who worked at Yokohama’s notorious brothel, which was popular with an international crowd.

You’ve painted a really vivid portrait of 1890’s Yokohama. Did you have to do a lot of research to get the historical aspect right? To what extent could you draw on your own experience of living in Japan?

To some extent, yes, I could draw on my own experiences of things like visiting temples and learning the language. Also, as I’ve said, roaming the port on my days off helped to give me a sense of the geography, and a feel for the maritime atmosphere which still exists in Yokohama.

But a lot of more traditional research was involved. I don’t think I appreciated when I started just how much, otherwise I might have reconsidered! As I said, I visited the Yokohama Archives of History and looked at those old copies of the Japan Mail, which were invaluable. Apart from the snippet about the young woman who drowned, they gave me a sense of the vibrancy of settlement life, and the contemporary political intrigue involving Japanese militant figures wanting to strengthen their grip on Korea. However, the single most important source for me was The Twice Risen Phoenix, a history of Yokohama by Burritt Sabin. Sabin was a U.S. Marine stationed in Yokohama at the end of World War II, who ended up marrying a Japanese woman and spending the rest of his life there. His book gave me everything from maps of the settlement in the 1890s to detailed accounts of the ex-pat theatre scene. Possibly without Sabin, I’d never have been able to write The Hotel Hokusai, so I’m indebted to him for his work.

On the Scottish side, I had to find out more about George Henry and Edward Hornel, who were key figures among the Glasgow Boys, financed by Alexander Reid to make a trip to Japan in 1893–94. Roger Billcliffe’s The Glasgow Boys was a terrific and comprehensive account, while Bill Smith’s Life and Work of E.A. Hornel added to my understanding of Hornel, his relationship with Henry, the trip to Japan and its aftermath. An article by Antonia Laurence-Allen and Helen Whiting, ‘Hornel’s Photographic Eye and the Influence of Japanese Photography’, gave me vital background on the link between photography and painting, while Ayako Ono’s thesis Japonisme in Britain, was another valuable source in understanding the appeal of Japan for these and other artists of the period. A lot of these I consulted only after moving back to Scotland in 2018, where I was lucky that my first job after returning, teaching English at the University of Glasgow, came with the perk of access to the reference library!

What was the writing process like?

Long! A lot of it began in notebooks that I would fill with tightly-packed handwriting, lots of crossings out and insertions. I felt the pen-and-paper approach was necessary to get into the minds of Han and Archie, who were themselves each keeping diary accounts of their time in Yokohama and investigation of Tsubaki’s death. Of course, it then had to be laboriously transferred to a document, at which point I started to fiddle with it. I battered out the final third of the first draft in that weirdest of lockdown spring/summers in 2020. It was very scrappy, but I felt brave enough to send it to a couple of friends, whose feedback helped me refine it into a second and then eventually a third draft by spring 2022. Between teaching work and parenting (my daughter has just turned 10), it’s always been a case of engineering or negotiating periods of writing time. Luckily, my wife has been tolerant of me disappearing into the bedroom and trying to hypnotise myself into 1890s Yokohama. Oh, and I also used music to help with this: especially César Franck’s Sonata for Violin and Piano, which I ended up slipping into the plot of the novel.

Why did you choose Ringwood Publishing?

One thing that attracted me to Ringwood was the fact that they were based in Glasgow. I liked the idea of having a publisher in the place I was living and which had a strong connection to the novel. I also thought The Hotel Hokusai might tally with Ringwood’s mission of publishing authors with a Scottish connection who may not find opportunities elsewhere. Part of fulfilling this pledge means that they accept unagented manuscripts, which was another major factor for me. There was no messing around with ‘send us your first 5000 words’, it was just ‘send us your book’. I liked that direct approach, and when I met Sandy Jamieson, I could see where it came from. Sandy is not a man for beating about bushes! Of course it didn’t happen overnight, and in fact it was six months after submitting the manuscript that I heard back saying my novel had passed to the next stage of the process. I had pretty much come to terms with not getting accepted, so hearing the news that they liked it enough to offer me a contract was a thrilling moment. Since signing the contract, I’ve only had good experiences with Ringwood. The editing team have been fantastic and helped me make significant improvements to the draft that was originally accepted. Likewise, on the marketing side, I feel very lucky to have benefitted from the energy and commitment of several talented people. Although Ringwood is a small operation, I would recommend it to anyone, especially first-time novelists looking for a publisher.

What drew you to Murder Mystery as a genre?

Well, I didn’t set out to write a murder mystery. I originally wanted to write a novel about the experience of adapting to life in a new country. However, in my experience, there’s nothing like a mystery to make a novel really enjoyable to read, so quite early on I decided to use one to drive my narrative. And as Hornel says to Han in the first chapter: ‘if you’re going to pick a crime to write about, you might as well go straight to murder’. Obviously, there’s a commercial element to this: As a first-time novelist trying to get published, it’s clear that murder mysteries tend to attract a readership. But there are lots of examples of crime as plot hook in novels that actually want to talk about other things as well. Graham Macrae Burnet’s novels spring to mind; Louise Welsh’s The Cutting Room, or, from further afield, Mario Vargas Llosa’s Death in the Andes. I’ve devoured loads of ‘pure’ crime novels, but I was always more interested in the kind that were harder to pin down.

In the book we are introduced to three Glasgow Boys: George Henry, Edward Hornel and the fictional Archie Nith. Why did you decide to create a fictional Glasgow Boy instead of using a real one?

Probably because fictional characters are easier to mess about with than real ones! No, seriously, even though I did a fair amount of research, my understanding of Henry and Hornel could only ever be based on looking at their paintings and the limited source material I could find. From this I could get a sense of their personalities: Hornel liked a party; he didn’t like children; Henry was more laid back with a very dry wit. They seemed to be something of a double act, each playing off the other. But apart from feeling that I didn’t quite know enough about them, it was this closeness that meant neither of them would work as a main protagonist. I needed a third man who was less rooted, who would go off befriending Korean migrants and trying to solve mysterious deaths. I tied this in with politics: Nith had to be a socialist, unconvinced by the kind of decorative art the Boys were expected to produce in Japan. If Nith is inspired by any real Glasgow Boy, it’s probably James Guthrie, who was the most driven to paint ordinary working people. But Guthrie stuck close to home in Scotland, whereas Nith is a wandering spirit. In some ways, he’s your typical repressed Victorian with an old-fashioned Scottish guilt complex thrown in. At the same time, he’s a progressive with a deep commitment to changing the world. There’s a fine line between idealism and naivety, and Nith is almost aware that he’s walking it. But he’s not aware that it’s a tightrope and there’s a long way to fall.

This story deals with the struggle of identity and blending into a foreign culture. What message do you hope readers will get from this book?

‘If it’s messages you’re after, then go to the shops.’ I don’t remember who said it, but I remember that quote being stuck on the wall on the 11th floor of the David Hume Tower, where I used to go for creative writing workshops as a student at Edinburgh Uni. I see what it’s getting at, but I think that’s a completely valid question that any writer has to face: What do you actually want the reader to take away from your book? In the case of The Hotel Hokusai, what I hope is that readers will have a heightened awareness of what creating a life from scratch in a new country actually involves. It would also please me if it gave them the youthful thrill of going somewhere completely new and seeing everything with fresh eyes. To paraphrase Italo Calvino in translation: ‘it’s not that we gain much understanding from travel, it’s just that it reactivates for a second the use of our eyes.’

Thanks for the chance to answer these questions. It’s been a pleasure!

If you haven’t yet grabbed your copy of The Hotel Hokusai, head here to get yours for £9.99 (plus P&P)!